Hip-hop at 50: Breaking pioneerTony 'Mr. Wave' Wesley recalls history of dance style News - In the South Bronx in the 1970s, a new kind of dance began to emerge and anyone could do it. It didn’t require much, maybe a piece of cardboard. Breaking, also known as breakdancing, was named after the breakbeats in hip-hop tracks that gave dancers a chance to show up and show off.

Hip-hop at 50: Breaking pioneerTony 'Mr. Wave' Wesley recalls history of dance style News - In the South Bronx in the 1970s, a new kind of dance began to emerge and anyone could do it. It didn’t require much, maybe a piece of cardboard. Breaking, also known as breakdancing, was named after the breakbeats in hip-hop tracks that gave dancers a chance to show up and show off.

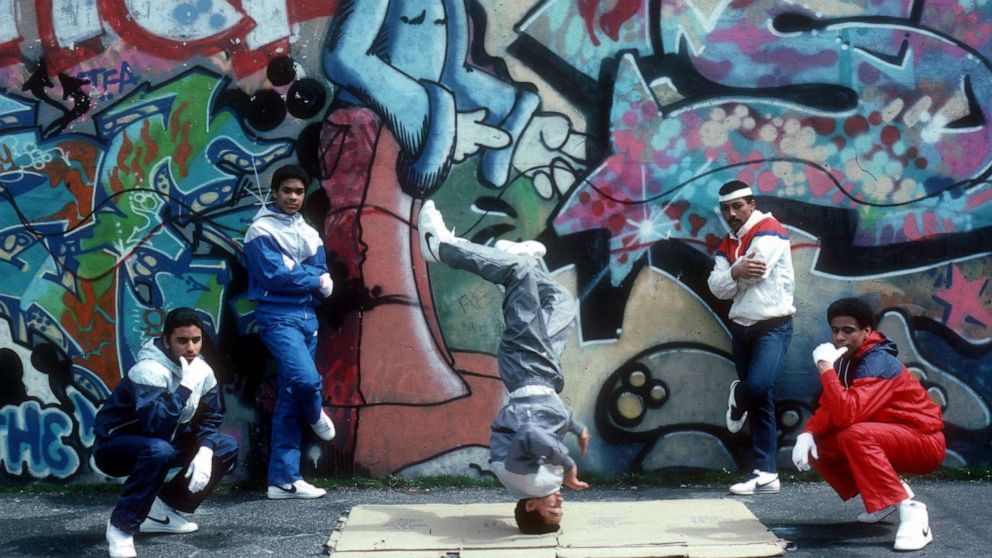

Breakdancing was marked by its signature athletic, high energy style that included head spins, power moves and freezes. It emerged alongside hip-hop; their shared histories closely intertwined. As hip-hop marks its 50th anniversary, ABC News spoke to famed break dancer Tony “Mr. Wave” Wesley, a fixture in the early hip-hop scene, at the Universal Hip Hop Museum in the Bronx, New York. “[New York] was the concrete jungle. That's what it was. And so just think about it, all of a sudden, thousands of kids learn these magnificent tools. You've never been to school for music. You've never been to dance school. You're not artists,” Wesley said. But despite not being an artist in the traditional sense, Wesley eventually got noticed by the dance group NYC Breakers. At the time, the group was so popular they “couldn’t walk the streets” without getting noticed, Wesley said. “The kids were so empowered, and they just wanted to be around us and we gave them that. I danced so much – 20, 30 times a day, every time I walked,” Wesley said. Wesley says his first show with the Breakers made him see “there was something bigger than the Bronx” for breaking. The group skyrocketed to fame and put this new style of dance on the map with performances on “Good Morning America,” variety TV show “Soul Train” and in the 1984 dance drama “Beat Street,” produced by Harry Belafonte. “Harry Belafonte, who you have to give praise to, he was the catalyst when he did the movie ‘Beat Street,’” Wesley said. In this April 1984, file photo, beakdancers are shown in Brooklyn, New York. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, FILE “So the evolution is what you're seeing, and this evolution is caused by cameras, film, YouTube. But, you know, it's evolving so much that the Olympics had to take a look at it,” Wesley said. For the first time ever, breakers from all over the world will compete for a gold medal at next year’s summer Olympics in Paris. “The challenge for them in the Olympics is to be able to score. You don't have to do 65 head spins. You have to be coordinated to where that number hits its mark. Similar to gymnastics, they flip, flip, flip. If they step one foot back, they lose a point,” Wesley said. Sunny Choi says she is ready for that challenge. The Queens-based breaker is one of the few Olympians chosen to represent the U.S. at the Olympics next year. Choi took a risk and left her job in the corporate world to pursue breaking – a risk that she says has paid off. “It feels so good, like, never look back,” Choi said. Choi, who is Korean American, says she has struggled with finding her place in hip-hop because she hasn’t always felt like she belonged or fit in. “What I've learned over time is, this whole culture has been so open and actually, warm and welcoming to me. And it was really just me telling myself I didn't belong,” Choi said. Most breaking pioneers have embraced the terms “b-boy” and b-girl” – separated by the sexes. Choi goes by “B-girl Sunny” in the breaking community, but that title hasn’t stopped her from winning battles against her fellow male competitors. As Choi prepares for the Olympics next year, it’s an opportunity not just for her, but for all young women and the next generation of breakers. In this 1980 file photo, a small crowd watches as a youth windmills on a piece of linoleum, as three youths sit with a boombox in Times Square, in New York. Archive Photos via Getty Images, FILE “I just feel like hopefully with everything that the Olympics brings in terms of exposure and money, that that also funnels back into the community. Because if you know the history, then you can take that and really move the art form in a direction that feels true as opposed to not knowing the history and then doing whatever you want with it. So I think it's helpful to kind of have that information, know the history, be able to carry that legacy forward,” Choi said. It's history that was made by people like Tony Wesley and will continue to live on in the Universal Hip Hop Museum. “The museum will inspire them to look backwards and see what we've done. I mean, I don't think anybody else will be able to dance with three presidents like I did – Bush, Reagan and Barack Obama. That's mine. You can't erase me,” Wesley said.